Public Participation

Team Playticipation: Ella Gutkowski, Dan Deutsch, Swetha Hiranya Venuturupalli

Professor Infield

REGIONPL 630

December 16, 2022

Playticipation: Participation Through Play

Introduction

“Forget what you know about engagement.”

That is the first chapter of Dream Play Build, a new book by urban planner James Rojas and urban designer John Kamp, where they break down their “Place It!” method of public participation through play in tremendous detail. After presenting on three different methods of public participation (storyboarding, gamification, and tactical urbanism) and attending public meetings that we felt were missing a certain spark, our group decided to synthesize our experiences into a workshop that sits a little outside of the box of conventional participation methods. Like Rojas and Kamp, we were inspired to change the way people think about engagement, and “Playticipation” was born. One of the main tenets of Playticipation is: creative processes work for all brands of thinking. Our vision for this method is to facilitate new connections and re-ignite the democratic process, all while having fun. By unlocking people’s creativity and quite literally putting everything on the table, Playticipation places interests over positions and levels the playing field of public engagement.

Our objectives are:

- Understand and analyze the key elements from the models (i.e. elements like sustainability and accessibility). This process helps us structure the ideas that the public think are essential for the city/town we live in.

- Create models based on the prototype of ideas we received from the workshop and have follow up meetings to see if we could envision their futures in the right way. These models would then help them experience the future cities we create for them…and with them.

Playticipation can be done with any group of people in any setting, but the most appropriate time in the comprehensive planning process is at the start of public engagement, or Community Visioning. This final report will review literature we found helpful in the preparation and evaluation of our process, detail outcomes, and provide next steps for what we would do had we run this workshop in a real-world setting.

Literature Review

Sherry Arnstein’s “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”:

Sherry Arnstein, the influential author of the journal article, “A Ladder of Citizen Participation,” discusses the significance of citizen impact as seen in participatory decision making. Our team related the concept of participation through play to the different rungs of the ladder. The placation rung, “allow[ing] have-nots to advise, but retain for the powerholders the continued right to decide[,]” somewhat describes the participant decision-making impact (Arnstein, 1969, 217). This section of the ladder, not specifically the placation rung, is tokenism, making a quick effort to involve impacted populations such as environmental justice communities. To elaborate on Arnstein’s words, our workshop participants are involved in the actual play-activity, but ultimately the final steps were left up to our team to deliberate on finalizing the design for the community.

Engagement Strategy Tips

The pamphlet created by the charity called, The Glass-House, is a “series of questions, prompts and snapshots'' we used to “think more strategically and holistically about how to develop a strategy for inviting local people and stakeholders into [our] design process” (The Glass-House, 2022). Being able to answer the questions of the Why’s, How’s, and What’s was key to our research and how we would evaluate our feedback from the workshop. The Glass-House brought up an excellent reminder in their pamphlet that pinpoints how Playticipation functions differently from traditional methods of participation: “collaborate design process is an iterative journey, and it is important to set out and continue to communicate through clear stages of decision-making that people can understand, and to which they can contribute'' (The Glass-House, 2022). Key questions from The Glass-House, 2022 pamphlet for evaluation were:

Why should people get involved?

How will engagement affect decision-making?

How can people get involved?

What can those engaging contribute?

What are your engagement objectives?

How will you use your engagement outputs?

How can engagement add social value?

We can not emphasize enough that the Playticipation workshop functions as one step of a part of the longitudinal process of planning a project. Our engagement objectives were to “generate and test ideas;” the creative nature of our activity unlocks the ability to explore and unlock local knowledge, give people the agency and ownership of their design, view communities in a brand new lens, and foster social capital (The Glass-House, 2022).

Case Study Context: Picture Main Street, Northampton, MA

Picture Main Street is a MassDOT Shared Streets and Spaces grant funded project set to finish in 2025 (Huisman, Streetsblog, 2021). The City of Northampton has embarked on a reconstruction project to invest in the future of Main Street. Design revisioning is taking place at the wide Main Street corridor from the intersections of Elm and West Streets, at the edge of the Smith College campus, to Market and Hawley Streets, and nearby the railroad viaduct. Our team was inspired by the design issues and design possibilities of this local project. Northampton created a ArcGIS StoryMap which can be found on the project website. The ArcGIS StoryMap outlined the design issues:

- need for ADA-accessible sidewalks and improved pedestrian crossings

- crashes due to bad traffic management

- poor visibility near crossing leading to serious injuries

- distance between vehicles and crosswalks is not maintained

- parking on Main Street has to be organized and parking for the disabled must be added.

Design possibilities were also outlined:

- variety of amenities in the Main Street; citizens have suggested three vehicle travel lanes, angled parking, wide sidewalks, and separated bike lanes

- need for a lush, continuous tree canopy for a healthier, more beautiful, and more resilient future

- balancing a wide range of pedestrian, biking, transit, and vehicle needs at the complex gateway intersection of Main/West/Elm/State.

Dream Play Build (James Rojas and John Kamp, 2022)

Urban planner James Rojas and urban designer John Kamp recently published Dream Play Build, a tell-all about “Place It!”, their method of public participation through play. To summarize, they schedule hour-long workshops at various community spaces, show up with a large assortment of found items and crafting materials, and ask people to simply play. Their warm-up exercise is usually a quick model-building exercise based on individual memory, and the community visioning portion challenges the group of participants to collectively build a model, addressing a given issue or challenge in the local built environment. Place is a multi-sensory idea, and “Place It!” uses multiple senses to engage participants in a fun engagement activity. Their deceivingly low-effort workshop is designed to provide an additional alternative to conventional participation methods. While researching for Playticipation, we discovered that, frankly, there aren’t many scholarly sources to back up why play is important in planning, which is why we we call it an emerging practice. We hope “Place It!” catches on in more communities, as we believe in the power of creativity to enact meaningful change.

In The Importance of creative participatory planning in the Public Place-making process, Elizelle J Cilliers and Wim Timmermans introduce the conceptual differences between “space” and “place,” which are admittedly interchangeable at times. Their first main idea, “places are spaces with meaning” is an appropriate foundation on which they build their discussion. They detail the contrast between different schools of thought in urban planning: conventional vs. place-making. The conventional schools of thought focus on economic growth and building things for people. The place-making perspective is more human-centric; we’re building spaces for people. “Place-making…is generally understood as a process that is part of urban design that makes places liveable and meaningful” (Flemming, 2007; PPS, 2008 in Cilliers and Timmermans, 2014). After detailing the elements of successful public spaces using a rubric from the Baltimore City Department of Planning, the authors demonstrate the importance of creative process in public participation. Earlier in the course, we defined public participation as a valuable element of democracy: collective power enacting change. “Meaningful participation in the decisions that affect people’s lives is an integral component of their sense of being sufficiently empowered to have some influence over the course of events that shape their lives” (Cilliers and Timmermans, 2014). Throughout our own collaborative process, we discovered that a sense of collective empowerment would be a valuable outcome of Playticipation. If we had been leading the actual Northampton community in a visioning workshop, I am confident that people would walk out not only having had fun, but feeling a sense of camaraderie and motivation to continue their own civic engagement practices. Cilliers and Timmermans conclude that creative participatory planning processes provide more interesting opportunities for public engagement, when supported by a thorough and appropriate stakeholder identification process. The link between creative participatory planning and place-making is the social capital that is built; “stakeholders become promoters and defenders of the space” (Cilliers and Timmermans, 2014). It is that very idea of collective ownership that leads to positive change.

Public Participation for 21st Century Democracy (Tina Nabatchi and Matt Leighninger, 2015) thoroughly explains the development of public participation, conflicting perspectives on what it means and how it ought to be used, and various methods for facilitators to utilize in practice. While we could apply our various themes (including Creativity, Interests vs Positions, and Scale) to much of this book, we found inspiration in their chapter on Participatory Planning in Land Use. We must recognize that people seek control over their surroundings. Whether that is put to good use or not is up to both planners and the communities they serve. “The ultimate goal of participation in planning and land use should be to strengthen the relationship between people and place and to change the way citizens affect - and are affected by - their physical surroundings” (Nabatchi and Leighninger, 2015). While it’s just one step in a larger process, Playticipation has the potential to help build the relationship between people and place to ultimately result in an outcome the community desires. Like Rojas and Kamp’s “Place It!” method, Playticipation prioritizes the importance of participants feeling heard over making sure every single element from the workshops is incorporated into the final plan; as planners and practitioners know, the client wants to see something that works. Creative methods like these encourage participants to create meaning behind abstract ideas, producing intangible results that are equally meaningful.

Interactive planning manual, James Rojas (2022)

Participation through play helps us think creatively and also taps our senses into creating tangible and intangible urban spaces for our future. This interactive experience focuses only on creating for the communities without any political barriers. The APA Equity guide suggests that for the public to give us any constructive criticism, none of the groups or communities must feel excluded or offended and this method not only does that but also helps us in understanding how they envision their futures. The idea of having different materials and scenarios brings complexity to the situation and helps the public understand what role a planner plays and how urban or regional spaces are made. Our reflections after the outcomes help us better understand what communities need with respect to one another. This process of having two exercises where they first work with one blank canvas and later where they work in correlation with other communities also talks about how interactive planning processes are done from the APA equity guide.

“Urban living assumes the life

of the inhabitants.

Urbanities rarely have the

opportunity to develop their

ideas on how to improve urban

living or create new ideas.” James Rojas

He focuses on creating space for their ideas for their communities and this has no barriers of age, income or race. By creating models where different people participate we create atmospheres of inclusion and also helps us make urban spaces for them with all inclusion. Participants feel the power of participation and get involved in the process while creating something for their societies.

Appendix i, Workshop plan

Results/Report-out

Outcomes

We observed minor and major details which could have a positive impact on our community through the models the class created during the workshop which helps us plan better.

1. Collective sense of ownership towards their towns and what they envision for their future. The citizens felt connected with what they create and this helps them understand the process better.

2. Citizen power with the participants feeling heard contributes to democracy. Our method is approached through play which gives them a space to showcase their thoughts on how they envision their neighborhoods through a creative process.

3. Positive outlook on one’s community through creativity and applying methods they think are possible. The two-part workshop gave participants a chance to design with a blank slate as well as analyze and create where complexities were involved.

4. Bridging gaps between groups of people that have different ideologies that don’t necessarily communicate regularly. Participants also had to work with different groups, taking the best of what their group offers to be able to design a space in togetherness including all communities. Working towards similar goals helped them take forward an overall design which meets the needs of all communities.

Themes

1. Scale

It’s hard to see the functions of a city at real-life scale. Bringing it down to human-scale or playing makes it more manageable. Play bridges gaps between ideas and puts them in context. The size helps both planners and the public to see the impact of one development has on the neighboring communities. It's extremely important for the participants to have a knowledge of the community and its structure, and this process helps with that.

2. Embodied Participation

We focus on participation through experience as it actively engages the mind and keeps it connected with the community in context. Experience of a space always helps us envision more and helps us recollect the nature of the place.

3. Building communities through structures:

Our role as planners and practitioners often takes architecture beyond the physical built environment; we’re facilitating connections between people. Once everyone understood what was expected, they immediately dove in. We observed distribution of labor and the organic formation of “leaders” amongst the community. We saw groups forming partnerships within seconds, spontaneously trying to figure out how to compromise space and materials. Several groups designated color-coding systems that made the final product easier to understand. Every participant established meaning behind abstract objects, and presented a cohesive vision of Picture Main Street. When we’re building models, we’re not just playing with toys…we’re building our future.

4. Interests over Positions:

What we as facilitators saw was a community of somewhat disparately connected individuals, coming together to create something magical. As the Playticipation team, we value interests over positions. According to Tina Nabatchi, “people with conflicting positions often have interests in common” and “when participation focuses on interests, discussions can become more cooperative, constructive, and productive” (Nabatchi and Leighninger, 2015). If your interests, both as an individual and as a community, aren’t reflecting honest feelings, it presents conflict. We want to know why people are feeling the way they feel. This is why the play method is an important precursor to subsequent meetings and interviews - creativity and collaboration unlock and uncover truths and perspectives people didn’t know they shared with others. A fundamental aspect of negotiating is separating interests from positions and in Playticipation, and we try to make negotiating fun. Our method assists in developing a particular narrative about the community we’re working with. By incorporating the aforementioned themes and more into our method, we’re empowering people to see themselves in their story in a different way.

5. Thicker participation through thinner activities:

Our quick-build activity structure lends itself to data collection that can be easily translatable into useful deliverables in the next stages of the planning process.

6. Creativity:

People were using and assigning symbols to objects in ways that wouldn’t be able to be seen without the aspect of play involved. For example, straws were trimmed with scissors and represented as street trees.

Evaluation

Evaluation criteria

Our team would know our workshop succeeded if people involved in the activity understood what the impact of their involvement was, minimal clarification was needed, and people felt heard and seen throughout the workshop.

Post-workshop Evaluation

While some aspects of the evaluation criteria were certainly met, as all first-time processes go, we made note of areas where things could improve. To start, our positives were that we saw that people were jumping at the opportunity to start playing with the materials on the tables. A paraphrased comment we heard over and over again through the class period was “this is so much fun!”. Without the aspect of play involved, we may not have seen this immediate spark of excitement and fascination. We used a bluetooth speaker to play upbeat music and set the “vibe” so to speak, and found that this made transitions from time point to time point in our agenda seamless. At the end of our workshop, we allotted time for questions, but there were none; we see this as another positive. This environment allowed all three of us to stay flexible as facilitators with our audience. If youth, marginalized groups, or generally different communities and special interests groups were involved, we believe this would be interesting and mesh well given the flexibility of the process.

Some points of improvement we found when evaluating our workshop begins with acknowledging that our instructions could have been more explicit (see appendix i for Workshop Plan details). We could have verbally and visually represented the instructions more clearly. When we transitioned to the second portion of our workshop, the actual team-build activity, it was not entirely clear to people that they were going to be working as a large group. Simply put, the larger group activity resulted in more complexities that our team, as facilitators, recognize and know that could have been improved upon in our instruction. Lastly, due to the need for space and materials for the workshop, our team was only able to run-through once with the space set up. Given this point, our team still practiced extensively outside of class time with scripts, assigning roles, and making sure all members were on the same page.

Next Steps![]()

Seeing as we were inspired by Rojas and Kamp’s “Place It!” method, our adaptation of next steps closely reflects their own process. As we briefly explained in the workshop and reviewed in more depth in our report-out presentation, our first course of action would be to publish all of the photos in an online album. Rojas and Kamp use flickr, so it makes the most sense to use that or a similar platform, linking to and from the Playticipation website. This is just one of many ways we would keep the process transparent, but it also shows the community and client the real joy that comes out of these workshops.

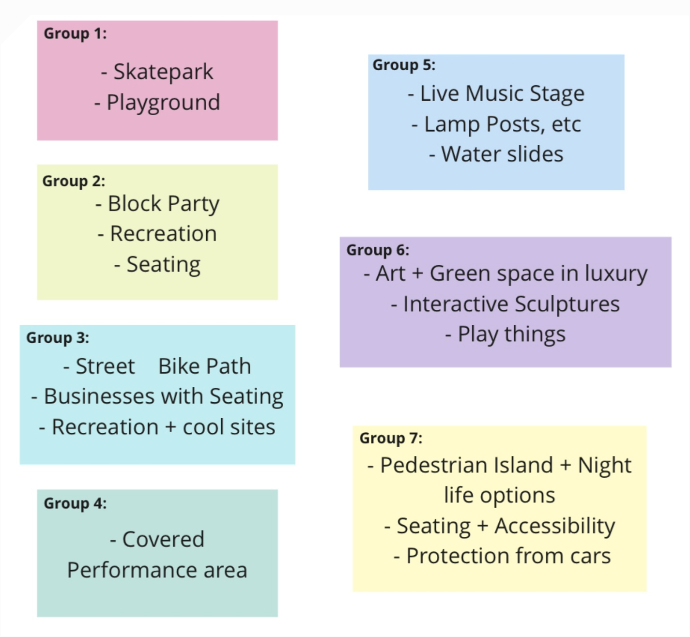

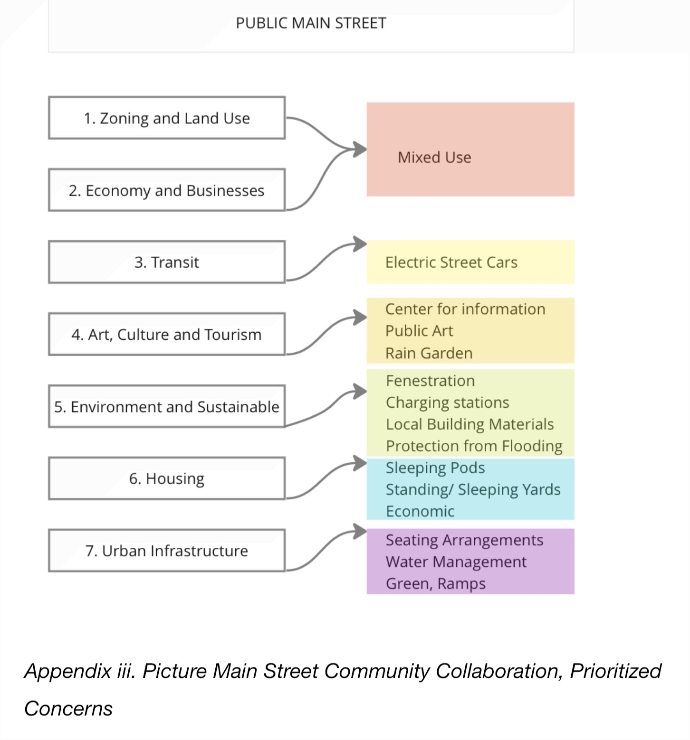

We would next take all the ideas that we gleaned from group share-outs and synthesize them into prioritized concerns (see appendices ii and iii). These concerns would be incorporated into a draft plan to shop around to interest groups and the general community through open houses and made accessible through our website. In addition to open houses, we feel that conducting individual interviews would strengthen a sense of accountability on our part, continuing to build trust with the community.

Appendix. Picture Main Street Community Collaboration, Prioritized Concerns

Interestingly, Rojas and Kamp found qualitative interviews done after the model-building process to have more negative tones. “While we initially found this to be discouraging, we realized that this dynamic served to further underscore the importance of using means other than just words to allow people to express themselves about their neighborhoods and cities” (Kamp and Rojas, 2022). Being as it may, individual interviews are an important communication touchpoint in a public participation process. The primary goal of these interviews would be to get feedback on what worked or may not have worked. We want to see if the community would be willing to participate in something like this again. After we’ve finished our research, drawn models and crunched the numbers, we would be ready to present a final plan to the governing body. Kamp and Rojas sum up their “Place It” method succinctly: “craft ideas for a better tomorrow,” and we believe Playticipation has the power to do the same.

Bibliography

Arnstein, Sherry. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Planning Association 35(4): 217.

Cillers, J. E., & Timmermans, W. 2014. “The importance of creative participatory planning in the public place-making process.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design (41): 413-429.

City of Northampton. 2022. “Downtown- Picture Main St. City of Northampton.” Accessed November 22, 2022. https://www.northamptonma.gov/2015/Downtown-Picture-Main-St.

City of Northampton. 2022, September. “Picture Main Street.” ArcGIS StoryMaps. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/4b996c75da2f4aaca58a1f0310424c77.

Huisman, Elena. 2022, March. “Northampton Resets Its Planning Process for Main Street Redesign.” Streetsblog Massachusetts. Accessed November 22, 2022. https://mass.streetsblog.org/2021/03/01/northampton-resets-its-planning-process-for-main-street-redesign/#:~:text=Northampton%20plans%20to%20reconstruct%20its,Streets%2C%20near%20the%20railroad%20viaduct.

Nabatchi, T., & Leighninger, M. (2015). Public participation: For 21st Century democracy. John WIley & Sons. 173, 244. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uma/deatil.action?docID=1895541

Rojas, J., & Kamp, J. (2022). Dream play build: Hands-on community engagement for enduring spaces and places. Island Press. 136, 167.

Rojas, J. (n.d.). Interactive planning manual James Rojas - growing up Boulder. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.growingupboulder.org/uploads/1/3/3/5/13350974/interactive_planning_manual.pdf

The Glass-House. 2022. “Designing Places with People: Tips for Your Community Engagement Strategy.” Accessed December 9, 2022. https://theglasshouse.org.uk/resources/designing-places-with-people-tips-for-your-community-engagement-strategy/.

Appendices

Appendix i Workshop Plan

Appendix ii Open Streets Northampton Visioning Exercise

Appendix iii Picture Main Street Community Collaboration, Prioritized Concerns